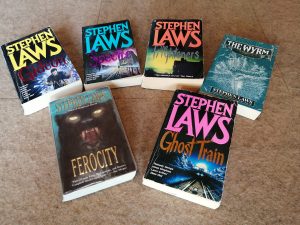

It’s my great pleasure to interview Stephen Laws today. Stephen is a master of the horror genre and a leading light for the British scene in the 1980s and 90s alongside greats like James Herbert and Ramsey Campbell, at a time when horror still had its own section in books shops, and publishers didn’t pass it off as psychological thrillers. He is also one of my favourite authors. For personal reasons, as you’ll see below, Stephen has been out of the public eye since his last novel Ferocity came out in 2007. We get into why and so much more below. And so without further ado, I give you… Stephen Laws.

Could you tell us about yourself?

Well, I was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in the North of England (where I still live). I went to Manor Park Technical School, having passed the eleven-plus examination, but didn’t enjoy my time there; particularly in the last year when the comprehensive system began and two streams of warring kid tribes converged and hell was let loose. I left with one GCSE O Level exam in English language and – as was expected in the late 60’s, got my first job at age 16 as an office boy in the Architects Department of Northumberland County Council. University was never an option. I worked 9 to 5 in local government (in a number of different office departments, specialising eventually in committee administration) until becoming a full time author twenty four years later. I’ve been married twice, with a daughter by my first wife and a son and daughter by my second wife, Mel.

How did you start writing horror fiction?

I’ve always written horror fiction (in one form or another) from a very early age. But that takes us, I suppose, into what ‘horror’ means as a ‘term’, I guess – and you’re probably as aware as any lover of the genre that this is a debate which has been going on for decades. What is ‘horror’? I’ve forgotten how many writers’ panels I’ve been on when that’s been discussed, but in the end I became so wary of the redundancy of explanation that I took my inspiration from Ramsey Campbell, who declares himself as ‘someone who writes horror’, and that’s that! That’s good enough for me. I’ve always had a love for ‘dangerous’ fiction, and I was writing adventure and scary stories when I was very small. I was asthmatic, and spent most winter months in bed. So I didn’t develop an interest in sport, but I did escape into the world of fiction via books, comics, television and cinema. An ex-primary school teacher of mine sent me my first typewritten-story some years ago (Miss Jeter) that she’d kept. I originally hammered it out on my Dad’s Imperial typewriter: ‘The Search for The Lost Treasure’ – in 1961 (aged 9). At around that time, I’d discovered Byker Library – and the works of Rider Haggard, Jules Verne, Conan Doyle and Bram Stoker. All dangerous adventure, but the real ‘danger’ came afterwards in stories that truly scared me – ‘horror’, I guess. I discovered Montague Summers’ ‘The Supernatural Omnibus’ – and some of the tales in there frightened the hell out of me. In particular, Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘An Incident of some strange Disturbances in Aungier Street’. I was convinced that this was a ‘true’ account. When I won Manor Park’s Technical School’s ‘Art’ Award in 1967 (You had to be ‘Top of The Year’ in 2 subjects. For me, that was Art and English). I was asked which book I would like as the school’s award. I chose the Montague Summers book – and it‘s still there on my bookshelf. A while back, on my first trip to Dublin with my wife, we hunted out Aungier Street and I found what I believe to have been the location of the story.

I’ve subsequently come to the belief that back then, struggling for breath during asthma attacks, I learned to deal with my night terrors by ‘making friends with the monsters’. Neil Snowdon recently suggested to me that Guillermo Del Toro also did this as a kid!

What would you consider to be the biggest influences on your writing style or approach to storytelling?

Any good writing is an influence on me, and it always has been. There’s nothing more invigorating than reading a story well told. My own passion has always, in longer fiction, been with narrative. In terms of ‘inspiration’ (rather than influence) there are all manner of writers who have had an effect over the years. I’m on record numerous times as having cited Richard Matheson and Nigel Kneale.

If you could co-author a book with another author, alive or dead? Who would it be and what would it be about?

If you could co-author a book with another author, alive or dead? Who would it be and what would it be about?

I just couldn’t do it. When I first began to write ‘seriously’, I was in a partnership with a pal as we tried to break into television, writing plays. But I don’t think that counts since we’re talking about literature. I’m just too much of my own man to collaborate on, say, a full novel. I’ve only had one experience of collaboration and that was with horror novelist Simon Clark, when our publishers organised a night in a haunted house. We were tasked to write a horror story based on our experience and the result was ‘Annabelle Says’, which was nominated for a British Fantasy Award. It was an extremely pleasurable writing experience because Simon is a terrific guy and an extremely talented writer, but it was an ‘experiment’.

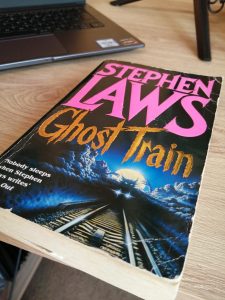

The north east of England features in varying degrees in your writing, from its country side in The Wyrm and Ferocity, Byker and Newcastle in Spectre, and it pops up at the end of Ghost Train, if I remember correctly. How has that part of the world shaped your imaginative landscape?

Enormously. The cliché is to ‘write what you know about’ and setting my fiction in the real world that I grew up in was a key aspect at the beginning. So yes, that’s been a big feature of my work – particularly Newcastle upon Tyne, where I live. I’ve given talks in the Ouseburn Valley over the years about that landscape (‘The Haunted Valley’). The Ouseburn Valley is a strange urban village in the middle of the City, by the River Tyne, and is the central setting for my novel Spectre.

Your brilliant book The Frighteners I would describe as a techno-supernatural. For me it’s a body-shock horror akin to Cronenberg’s best work. Where did the idea come from/ and looking back, if you rewrote it today how might the novel change?

Your brilliant book The Frighteners I would describe as a techno-supernatural. For me it’s a body-shock horror akin to Cronenberg’s best work. Where did the idea come from/ and looking back, if you rewrote it today how might the novel change?

You’re not the first to make a Cronenberg comparison about The Frighteners and I take that as a great compliment for which I thank you. But the novel wasn’t particularly inspired by him or his work. The ‘good and evil’ element that was so central to Stevenson’s ‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ was really the starting point for me, and that’s why there are explicit references and quotes in each section of the book. This was my fourth novel and I was actively trying to ring the changes on a number of horror tropes at the time. I wanted to create a crime-thriller with a strong and emerging supernatural element. Get Carter meets The Exorcist, I suppose. I also sneaked in a homage to Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass and the Pit- which is most obvious in a semi-quote reference in the last line of the book which alludes to the American re-titling of the Hammer film. The character of ‘Sir James Callender’, by the way is very much based on the actor Andre Morell, who not only played Professor Quatermass in the 3rd TV series, but was also ‘Sir James Forbes’ in Hammer’s Plague of the Zombies. I had a meeting with Andre’s son Jason some years back, and was able to give him a copy of the novel and pointed out the fact. It was a very emotional meeting. I wouldn’t rewrite the book. But so much has changed in technology since then. The internet, the mobile phone.

Tell us about your biggest achievement or proudest writing moment to date?

Every time a novel, novella or short story appears is a ‘proud moment’ and one hopes of course that it will have the intended effect on a reader. I’ve always felt an element of personal growth with each novel published. Winning a British Fantasy Award for ‘The Song My Sister Sang’ and first prize in the Sunday Sun newspaper short story competition for ‘One for the Road’ (an electric typewriter!) still sticks in my mind.

Now tell us about your lowest moment and how you overcame it? Go on, be a hero.

My absence from the genre for some years was difficult, and is still talked about by those ‘not in the know’; so I’ll take the opportunity again to say that there were two issues involved there. Firstly, my son Jonathan was diagnosed autistic, and I had to take time out to address his needs. We became part of a new programme called I-Can, where a parent and child are involved with a specialist teacher on what was then a new programme called the ‘Play Way’. (Jon and I were test subjects in the early days of the programme, and we both feature in a textbook on that programme called ‘Communication Counts’ by Fleur Griffith). Emotionally and physically, that was all encompassing – and it coincided with the collapse of horror fiction in the late 90’s. At that time, I was unable to invest the energy and emotion that I’ve always brought to my writing when I needed to give everything to my son, my daughter and my wife. Jonathan eventually graduated from Aberystwyth University with a Mathematics Degree and is now a successful data analyst.

Your last novel was Ferocity in 2007. Several of your novels are being republished, such as Ghost Train by Valencourt and The Frighteners by Bloodshot Books. Have you any plans for a new novel?

I have three novel manuscripts in a drawer, and I keep going back to them. In the meantime, I produce short stories, novellas or articles when I’m asked.

I’ve seen photos of you hanging around with James Herbert and Ramsay Campbell. How would you say horror has changed over the decades?

Jim Herbert didn’t suffer fools gladly, so I was privileged to be called a friend. His early novels were inspirations when I first started to write seriously. Ramsey Campbell is a dear friend, and he suffers this fool gladly. I’ve known him for decades and we’ve had great times together. His book The Pretence is dedicated to my wife Mel and I. He’s absolutely ‘one of a kind’ and if you haven’t read it yet, I’d heartily recommend that you pick up ‘Ramsey Campbell, Absolutely’ – 40 Years of Essays, Revised and Expanded (PS Publishing). It’s inspirational. How has horror changed? Well, it depends whether you’re talking about form, content, previous and current attitude. You’ve asked a parallel question below, so I’ll address that there.

Your writing is very cinematic, from the plot, the action and through to protagonists who go through profound change. Which of your novels would you most like to see turned into a movie? And who would you have direct and star in it?

For novels, I’ve always worked from an outline written in present tense, pretty much the way you would describe a film that you’ve just seen; so that probably accounts for the ‘cinematic’ aspect that you’ve described. Some writers pre-plan their work, others like to work from a blank page and enjoy seeing what happens. Some writers concentrate on character and are less concerned with narrative. I discovered a long time ago in a breakthrough moment that I was a ‘Story’ man and that pre-planning was what worked for me: the production of a present-tense, skeletal structure with beginning, middle and end – simply stating what was going to happen next. (As if you were telling someone the story of a film you saw last night). But not, I hasten to add, in great detail. If a character has to have a ‘revelatory moment’ that leads to a bad decision that results in a car crash, that’s all I need from a construction point of view. When it comes to the fleshing out of the skeleton, I can work out what that revelatory moment will be. The point is – I’ve created the skeletal structure of that story and now I’ll enjoy developing what were originally shadowy characters as the story evolves along my pre-planned lines. And it’s more often than not that the next stage here becomes the most exciting. In writing and developing a realistic character (more important in supernatural and horror fiction than in so-called straight literature, in my view) I suddenly realise that this emerging character would not do what I’ve pre-planned him to do. I can’t bend his will to fit the pre-planned story I have in mind. I now have to find a way of getting from A to C in the story – not through B, as I’d planned – but through a different and more credible route than originally conceived. (Hope this makes sense). Dealing with this kind of issue brings life to your story and your characters, engages you in a way you’d never thought possible, and you’ll know that you’ve got it right. So – as you’ll see, I’m a ‘story’ man and my characters emerge in the telling of that story. This doesn’t work for some writers at all, but is essential for me.

You’ve so much experience as an author. What’s the hardest thing about being an author? Has it changed over the years?

Being an author hasn’t changed. It still requires the same fortitude and purpose of applying yourself. It was always hard, and it continues to be hard in a changing landscape. I’m old school in that my first novel was published in 1985. I didn’t have an agent, so I followed the advice of the Writers and Artists Yearbook and sent a sample chapter to a number of publishers, most of whom turned it down. But when a publisher showed interest, I sent the entire novel, was called in for a meeting with an editor – and Ghost Train was eventually published. I say ‘old school’ because I was lucky enough to have a good relationship with most of my editors and their input was invaluable. It also helped me to learn my craft over the years, serving an apprenticeship of sorts as I moved from novel to novel. Back then, self publishing was just not the done thing. One avoided ‘Vanity Press’ and vanity publishing like the kiss of death. Everything’s changed now. Anyone can write and publish a book today. That’s a good thing and a bad thing depending on the way you look at it. Learning one’s craft with the discipline and positive input of a significant editor was an invaluable thing for me. Not just the simple things like pointing out that one of your characters has blue eyes on page 24 and brown eyes on page 87, but challenging your own position on aspects of structure or narrative if he or she thinks that they have a point to make that will improve the work. If you’re completely sure of your position it’s good to argue and make your case, because that can often make you rethink where you’re coming from. I’ve been lucky enough to have had mostly positive input from all of my editors over the years, and been grateful when it’s pointed out that there may be a fault with a narrative thread; even better when you can show that the fault lies in the editor’s perception and not your own! In recent times, I’ve read self-published work that could have done with that learning process, lacking even a good line edit and basic grammar. I’ve just finished something that was jaw-dropping in its ineptitude. But on the other hand, I’ve read self published material that is simply outstanding. I should also say that I’ve recently read a horror novel by a mainstream publisher that was so clumsy in its exposition and with such clunky dialogue that I had to force myself to read on past the half way stage. Fortunately, in horror today there is just so much good stuff being written that it reaffirms just how potent and powerful the genre remains. I’d highly recommend Adam Nevill (The Reddening is terrific), Tim Lebbon and Paul Tremblay. If they don’t mind me calling them ‘old timers’, we still have Mark Morris, Stephen Volk, Paul Finch and others producing stand out fiction.

Everything’s changed now. Anyone can write and publish a book today. That’s a good thing and a bad thing depending on the way you look at it. Learning one’s craft with the discipline and positive input of a significant editor was an invaluable thing for me. Not just the simple things like pointing out that one of your characters has blue eyes on page 24 and brown eyes on page 87, but challenging your own position on aspects of structure or narrative if he or she thinks that they have a point to make that will improve the work. If you’re completely sure of your position it’s good to argue and make your case, because that can often make you rethink where you’re coming from. I’ve been lucky enough to have had mostly positive input from all of my editors over the years, and been grateful when it’s pointed out that there may be a fault with a narrative thread; even better when you can show that the fault lies in the editor’s perception and not your own! In recent times, I’ve read self-published work that could have done with that learning process, lacking even a good line edit and basic grammar. I’ve just finished something that was jaw-dropping in its ineptitude. But on the other hand, I’ve read self published material that is simply outstanding. I should also say that I’ve recently read a horror novel by a mainstream publisher that was so clumsy in its exposition and with such clunky dialogue that I had to force myself to read on past the half way stage. Fortunately, in horror today there is just so much good stuff being written that it reaffirms just how potent and powerful the genre remains. I’d highly recommend Adam Nevill (The Reddening is terrific), Tim Lebbon and Paul Tremblay. If they don’t mind me calling them ‘old timers’, we still have Mark Morris, Stephen Volk, Paul Finch and others producing stand out fiction.

What’s the best thing about being an author?

Is there a best thing? It’s great to have been published and to have achieved some success in the genre – and believe me it was a terribly long and hard struggle to get there. But I was driven by the urge to write; something that’s been with me since I was six years old. I’ve stayed passionate about horror with its frequent blur between reality and fantasy, between mind and matter, and it’s often a difficult field to work in. But it’s my field and I love it. I suppose the best thing will always be having a positive reader reaction to any fiction that you’ve written and the knowledge that you’ve managed to make that connection with a reader.

What’s your all-time favourite horror movie and why?

Wasn’t it Martin Scorsese who was asked a similar question and came up with a list of about thirty films? There are so many horror films that I love. Thinking of the films that I return to regularly – that would include the original The Haunting by Robert Wise (1963), Night of the Demon by Jacques Tourneur (1957), Night of the Living Dead by George Romero (1968) and Terence Fisher’s Dracula (1957) – but this list could go on for several pages.

What’s the first horror novel you remember reading? What impression did it make on you?

The first out-and-out horror novel was Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which I read over a couple of rainy days in Byker, Newcastle when I was very young. It completely immersed me. But I’d been reading novels with elements of horror even earlier than that.

What are you reading right now?

‘Warts and All’ by Mark Morris (which he very kindly sent to me while I was recovering from a burst appendix and peritonitis), ‘Growing Things’ by Paul Tremblay, ‘Send in the Clowns’ (The Yo Yo Life of Ian Hendry) by Gabriel Hershman. I’m re-reading ‘The Witch of Prague and Other Stories’ by F. Marion Crawford (and in a perverse way I’m loving his dense paragraphs filled with semi colons. ‘Sleep No More’ (Railway, Canal and Other Stories of the Supernatural) by L.T.C. Rolt – and very much looking forward to Shadowplay by Joseph O’Connor. My ‘to be read’ pile is always a mile high. I still can’t believe that there are would-be writers out there who don’t read fiction.

Which book by another author do you wish you had written, and why?

Ghost Story by Peter Straub and Salem’s Lot by Stephen King. I read both novels when they were first published, and I still return to them.

Which monster from fiction – books, TV or film – would you most like to be and why?

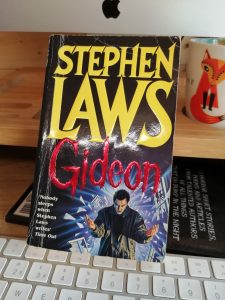

GORGO. Because he gets up to all kinds of mischief, then gets rescued by his mother at the end when she trashes London. Just in case that sounds like I have a mother fixation, I’d better think of another one. DRACULA – in the movies – because he’s iconic, and he always managed to come back again no matter how many times he’s been staked. By the way, if you check out the first UK hardback and paperback edition of my vampire novel Gideon (Hodder and Stoughton/New English Library) that’s me as the model for the vampire on the front cover.

Where did the idea for your last book come from?

I couldn’t answer that one in a straight forward manner because all of my work comes from a multiplicity of ‘ideas’. I keep detailed notebooks and if something occurs to me then I’ll write it down, usually with no idea why it’s so intriguing. Later, as I write more notes I may see that it’s linked in some way to other ‘ideas’ and that’s when the narrative begins to emerge. It’s a different matter with short stories, I think. I scribbled down a note once when I overheard a young daughter talking to her mother in broad Geordie dialect on the top deck of a double decker bus. The note stayed there, and I kept coming back to it. Twenty five years later, I eventually found the ‘connect’ that I was looking for, wrote the story and it was published in Johnny Mains’ ‘Best British Horror (2015) (‘The Slista’)

What book of yours should people start with?

The first one – Ghost Train – and then work your way through. What else?

Where can people stalk you online like a serial killer?

My website is at – www.stephenlaws.com But no serial killers, please.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

What I should highlight is the new society that I’ve created with Neil Snowdon called Novocastria Macabre. Based in Newcastle, it’s a celebration of all things macabre, supernatural, thrilling, ghostly and horrific in literature, cinema and television. As well as our own events, we want to provide a ‘hub’ of activity for other specialist organisations operating in the North up here in the ‘genre’ areas that we all love. So far we’ve had very successful interviews on stage at Neville Hall in our ‘An Evening with …’ sessions; most recently featuring John Connolly (author of the Charlie Parker crime novels, but also writing superb supernatural and horror tales), Stephen Gallagher – whose third Sebastian Becker novel had just been published (‘The Authentic William James’), and which I can’t praise highly enough. Our ‘joint events’ have featured Stephen Volk, David Pirie, Rob Shearman- and Angela Slatter. The latter two artists appeared at the wonderful Black Gate Museum. We’re also keen to champion the work of writers from the past who may be well known to those of us who grew up with horror, but who may be less familiar to a younger audience; such as Algernon Blackwood, Joseph Payne Brennan, Fritz Leiber, Theodore Sturgeon, John Fenwick Blackburn etc .This is quite a long list. Indeed, I’ve written a celebratory introduction for one of Blackburn’s novels (‘Our Lady of Pain’). Neil and I were discussing the possibility of an Arthur Machen ‘event’ with a specialist writer/performer, but unfortunately the corona virus lockdown brought everything to a halt. When we’re out of lockdown, we’ll pick up where we left off, with other great events lined up – interviews, talks, lectures, film and TV screenings; and I’m writing a One-Act supernatural play to premiere at Neville Hall.

Dan: this sounds like a brilliant venture. I will check it out. Thanks for your time today.

Check out Stephens wonderful novels here:

Your brilliant book The Frighteners I would describe as a techno-supernatural. For me it’s a body-shock horror akin to Cronenberg’s best work. Where did the idea come from/ and looking back, if you rewrote it today how might the novel change?

Your brilliant book The Frighteners I would describe as a techno-supernatural. For me it’s a body-shock horror akin to Cronenberg’s best work. Where did the idea come from/ and looking back, if you rewrote it today how might the novel change?