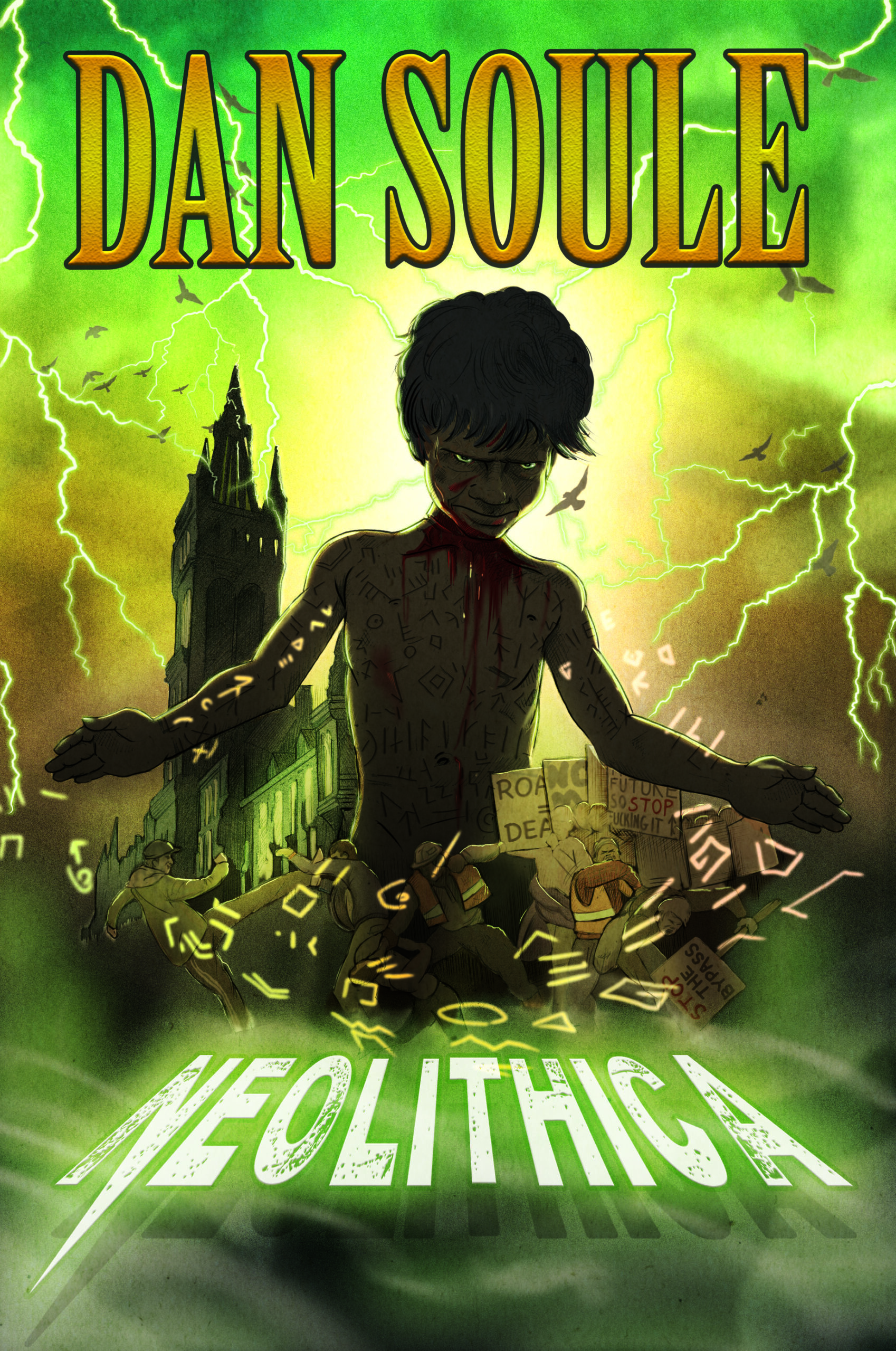

Trying a new author is a bit of a risk. Are you going to throw away your money? Will you like their style and tone? Amazon, Apple Books and the like give us a sneak peek. Here, I wanted to give you a little more. Below you’ll find the Blurb, the Prologue and first four chapters of my debut novel Neolithica. Have a read. I hope you get hooked and want to see more. Now brace yourself…

Blurb

What happens when the archaeological find of a lifetime becomes a threat to life itself?

After the death of her husband, Professor Mirin Hassan wants life to return to normal for her and her son. But when construction workers discover an ancient body in a Scottish peat bog, Mirin has no choice but to investigate the intricately tattooed Neolithic boy. Media attention and professional rivalries become the least of her worries because something other than cameras followed the corpse back to the university. Something beyond reason. Something evil. Something Mirin and the entire world will wish had stayed buried.

A must read horror for fans of classic paperback horror, Neolithica escalates to a shattering conclusion, in which the lives of a mother and son are intertwined with the fate of all humanity. A novel as epic in its vision as it is up close and personal with its frights. You won’t want to miss this one.

“Neolithica is a masterful meditation on horror and grief – A cult horror smash, which conjures up the very best from Hutson and Herbert – a terrifying must read for all horror fans!”

Bram Stoker shortlisted author Ross Jeffery

Prologue

Tk’lo, Bear Paw, sat cross-legged staring into the fire, embers dancing into the endless night sky. He was warm enough under fur blankets, one of beaver, the other of wolf, and looked up at the other blanket he sat beneath: a sky of countless stars, so many that they were like the froth of river rapids. His people believed they had been born from the tumult of those churning heavenly waters, and to the waters they would return, once the spirit of this body was done with the world. Tk’lo, an old man, the oldest of his tribe, was not sure he still believed this, though he sang the old stories, even the ones his children, and their children, could never remember because they could no longer walk the songlines.

He waited now on the edge of the known, where the land remained as it always had. The trees at the perimeter of the snow-covered clearing marked the ever-encroaching boundary that ate into their world. As the fire crackled, sending up another spray of dancing sparks, a growl came from the treeline.

Tk’lo did not reach for the stone knife at his hip, or for the stone axe lying beside him, which he had learnt to copy from the one he’d traded with the milk drinkers many years ago. It was the same type of axe those foreign people had used to cut down all the trees and take the memories in their songlines, the ones only Tk’lo could remember.

The tribe was once a great melody of life, moving through the land singing together. Now they were barely more than a few families left with a handful of songs. Each year more of them walked beyond the treeline and into the land of no memories to eat grass and drink milk. Tk’lo let out a hollow laugh at the idea of drinking milk. He had tried it several times, but he would always end up behind a bush farting like a giant urus bull.

Another growl came from the treeline.

“Ha! You try drinking milk, Ulv’nor,” he joked. If the spirit of the great wolf was there, it made no reply. He pulled the beaver blanket around his shoulders a little tighter.

He looked skyward one last time and shuddered. Why, Tk’lo could not be sure. Perhaps it was the glint of reflected light in the eyes shining from the darkness of the treeline. There was something in the great black river that the other tribespeople could not see. Even after he and his brothers brought news of it back, carrying a dark song on their lips, they were loath to sing, they still were not believed.

And now, the last of his people had moved into colder lands to try to learn the songs of others like them, those moving with the migrating animals and the changing of the seasons. The dark song and its warning would die with him. Tk’lo looked into its eyes staring from the darkness behind the stars; the stars shone with the light of another world beyond this one, glinting off the thing’s obsidian scales. Its tail curled around their world. Its serpent’s tongue licked the air, tasting the avarice of a place of no true songs.

The crow croaked as it flew over Tk’lo’s head. It opened its wings, turning on the air, coming to rest by the fire as a pack of wolves padded from the treeline. Their heads hung low. The sound of their growls rumbled with the power of a gathering wave. The crow screeched again and the old man kicked out with his arthritic foot. He only succeeded in making the crow hop back and make a noise that sounded like a laugh.

“You can wait for your meal,” Tk’lo told the crow, knowing the crow was here for him. They always knew when death was coming.

Tk’lo’s father had once said to him he ‘wished to sit by the fire tonight with Ulv’nor’, that it was time to sing with him. Better that an old man feed the wolves and crows than slow down his tribe and take food from the young ones. They all needed their strength in these meagre times, and learning new songs would not be easy.

As the growls grew louder, Tk’lo began to sing the song of the great wolf.

From the night of the land with no songs came the boy with eyes black as the scales of the thing from behind the stars. Tk’lo remembered the boy and felt the bile rise, burning his old throat. Now, he reached for his blade. He wished it was a blade of black stone.

Naked in the snow, and with wolves at his flanks and a crow at his feet, the boy smiled without kindness through fire-cast shadows, which made the small markings on his skin come alive. The boy looked beyond the old man in the direction his tribe had fled.

Tk’lo, finding a strength that had long since left his frail body, rose from his fur blankets. They fell to the ground like heavy snowflakes. He had stayed here to die and knew that what he did was nothing more than a futile gesture of a dying old man, but still he gave one last cry of battle.

The crow let out a laughing caw, and the boy grinned with fire dancing in his black eyes.

BOOK I

“What we call civilised consciousness has steadily separated itself from the basic instincts. But these instincts have not disappeared.”

Carl Jung

“To be able to forget means sanity.”

Jack London, Star Rover

Chapter 1

Mary loved the sound of the pigeons talking together. They said only good things, and to her looked very like the people she saw in Glasgow. Some were beautiful and clean, with plump chests and nice feathers. Others, Mary thought, looked more like her: dirty, old, maybe with a toe or an eye missing. All of them, however, had a rainbow around their necks. The thought made her happy, stood in the middle of Sauchiehall Street, a hundred birds flocking around her, and a dozen more perched on her arms, shoulders, and the woolly hat on her head. She fed them bread while the people of the city rushed around her, parting like the waters of a river around a rock.

Mary did so like to catch up on all the pigeons’ news, cooing to them softly as they pecked bread from her hands and from the crumbs she’d scattered around her feet.

Then, as if she had said something wrong, they all took flight with a fricative trill of wings. Mary felt a little sad her friends had gone. She was about to pick up all of her things, packed neatly into a large, square polyethylene shopping bag, when the reason for her friends leaving cocked its black head at her and croaked.

“Stupid Mary,” the crow said, hopping closer.

Mary hated crows. Nasty things they were. Never a nice word to say about anyone. Not like pigeons or most dogs. More like cats but less sarcastic. Mary ignored it and picked up her heavy bag.

“Don’t be stupid, Stupid Mary,” the crow laughed, but it wasn’t a nice laugh. It reminded her of the laugh the cruel porter used to make back when Mary was younger and lived in Lennoxcastle. The porter was called Eddie. She’d never met a nice Eddie and guessed it was the name given to nasty people. In fact, Mary would guess every crow in the whole world was called Eddie, even the girl crows.

“Go ‘way, crow,” she told it with a pouting scowl.

“Where you going to go, Stupid Mary? You haven’t got a home. You haven’t even got a brain.” The crow thought this was very fun and hopped in Mary’s way so she couldn’t get away.

“Don’t want to talk to you,” Mary said, trying to shuffle to the side, but the crow hopped laterally to block her way.

“Stupid Mary, quite contrary. Just trying to help.”

“You’ve helped no one, horrid crow.” Mary made a break for it, using her bag to knock the crow away and join the stream of people. The crow wouldn’t follow her there. Instead, it fluttered into the air, shouting after her.

“Run away, Stupid Mary. It won’t matter.”

Then, stretching out the black cloak of his wings, the crow was gone.

Chapter 2

It wasn’t a good day. No, actually, it was a great day, even in the Scottish rain, which had begun to feel like a familiar friend to Stephen. Driech was the word the guys on the site used, and Stephen liked it. In his mouth, the word had the quality of the day: grey and with a touch of morose acceptance. It shouldn’t be something to like, but he did. More and more he had felt affinity for this rugged place. Its landscape and its people had rougher edges than the soft, lilting Nottinghamshire countryside he had grown up in south of the border.

Stephen’s whole family were settling in nicely. The girls had started at the new school in Kirkintilloch at the beginning of the school year in August. A bit of a change for them from the English timetable. He wondered at how adaptable his girls were, even hearing a few Scottish notes in their accents already. Janet, his wife, had found a job in a good Glasgow accountancy firm. And for Stephen there was plenty of work on the horizon. The risk of the move seemed to have paid off. The cost of living was amazing compared to the southeast of England and London in particular, where they had moved from. They had initially expected to buy in one of the upmarket suburbs around Glasgow, Bearsden, or Milngavie. Instead, they had fallen in love with a house and then the small village in which it sat, Milton of Campsie, lying at the foot of the Campsie Fells. When they drove toward the place, the fells had risen dramatically behind the village.

The house was large and a little quirky, like their decision to move from everything they knew in England. And the fact that the property was a quarter the price of similar properties around London didn’t hurt either. Even better, the local high school was a high-performing comprehensive, and so they didn’t even have to pay for schooling.

They were having the best of all worlds. They’d quickly stopped telling themselves they could go home to England at any time, back to the long commute, back to all the frantic pace of life and the high cost of living. They were putting down roots, making friends, feeling at home. Stephen thought all these things as he turned off the motorway, a coffee in one hand and the promotional brochure and the plan of works sitting on the passenger seat next to him in the Range Rover.

‘Bringing us closer to nature’ read the brochure’s title. It didn’t much appeal to Stephen. The advertising copy was a little contrived, but that wasn’t his department. He was a civil engineer and the project manager, and this wasn’t a big job anyway. Another six months to go, nine months maximum.

A local environmental group had taken exception to the project. There had been a minor bit of local press coverage and a small piece on the national Scottish news. Hardly anything, really. The environmentalists were a regular fixture at the site entrance and were really quite friendly. Stephen knew several of them by name. There was Meredith, the lady with the grey, curly hair, always in a stripy jumper. Susie, a young, pretty girl in her early twenties, who would have been quite a stunner, Stephen thought, if it wasn’t for those thick dreadlocks she sported. Still, it takes all sorts. And there was Jerry, a dumpy man on the wrong side of middle age who fancied himself as something of a firebrand, shop steward type. He’d mellowed when he saw Stephen’s Derby County woolly hat one cold day. Apparently, Jerry’s father had been from Derby and it was still his team. Well, apart from Glasgow Rangers, of course.

Meredith, Susie, Jerry, and a handful of others were there every morning with their flasks of tea and homemade placards. The group would have a go at a protest chant in the morning and usually another when the heavy vehicles on the site stopped for lunch. By the evening, though, their numbers had normally thinned out, and instead of chanting, both sides would wave each other off. The whole thing was rather convivial. Okay, they didn’t see eye to eye on the need for the project, but Stephen could see where they were coming from. In a way, they both kind of wanted the same thing. It was only a small road, cutting into a little bit of the peat land. The protesters’ main objection was the destruction of a historic natural habitat, peat being laid down over thousands of years. Stephen’s company were building to help the National Trust and the Department for the Environment bring more people to the natural world to promote conservation. Their ultimate goals were the same. As such, even the protesters made Stephen feel good about his decision to move the whole family to Scotland.

Just one small thing played on his mind this morning. Last week, his eldest, Tilly, had come home with a dark cloud over her. Janet dug into it. Matilda was a forthright nine-year-old, confident in her opinions, which Stephen knew all too well could cause an argument at home from time to time. There is nothing quite as maddening as a nine-year-old who knows the answer to everything.

It seemed during a playground game one of Tilly’s new friends had said for her to “stop being so English.” Tilly didn’t know exactly what that meant, but knew it wasn’t a compliment. Stephen had had a similar experience two months back with one of the workmen on a different project. He was an older man with a lot of building experience and set in his ways. Stephen required the new health and safety paperwork filled out in the new format. The old-timer, Alistair, didn’t see the importance of it or couldn’t be bothered. Alistair strongly resisted completing the new paperwork. Holding his ground, Stephen made his case again, but Alistair still wouldn’t listen. Stephen had no other choice but to put his foot down and insist. Alistair had walked away, and Stephen heard him mutter, “English twat.” Alistair was well liked; Stephen got his own way, and so he let it go. Though he did ask for Alistair not to be selected for any of his further projects.

Stephen and Janet talked about the work incident and Tilly’s playground problems at home, deciding in the end they weren’t anything to be too concerned over. There were always a few bigots wherever you go. Weighing it all up, it was a small price to pay for the benefits of their new life. They were more relaxed, had more time with the kids in a great house set within breath-taking nature, and all with money in the bank.

As he passed the protesters to pull onto the site, Stephen slowed the car and gave them a wee wave. A couple of them waved back. Jerry good-naturedly brandished his placard, and the others cheered with small plastic thermos cups of tea in their hands.

The smooth surface of the road gave way to the compacted gravel of the work site. Stephen’s four-by-four suspension lolled him up and down like a boat entering the choppy waters on the edge of a storm.

He could see the site ahead. Most of the team had already started work. Willie, though the guys pronounced that more like woolly, was in the earthmover about to cut into a swath of dark peat. The huge yellow claw gouged into the bank of ancient peatland, ripping a bucket of earth into the air. Clods of dark brown soil dripped from it like decaying flesh.

In his temperature-controlled cabin, Stephen felt a gust of stagnant cold air brush his skin. What the hell was that smell? It was like someone had opened a tomb. His flesh goose-bumped.

Nausea surged from the pit of his stomach, and his sphincter tightened in fear. At that same moment, the Range Rover cut out. Everything electrical went dead. The satellite navigation turned black. Dashboard gauges fell limp and lifeless. The digger, with its monstrous claw, along with all the other machinery on the site, also ground to a halt. In unison with their machinery, all the builders had stopped dead. It was as though they were all feeling the same thing Stephen was. What colour they had in their faces on this driech morning drained away, and the sky darkened with a rumble of thunder.

His Range Rover still moving, luckily not at speed, Stephen finally remembered to apply the brakes to the three tons of lumbering metal. The brake pedal wouldn’t respond. He pumped it twice, feeling the panic of falling in a dream and missing the final hold before oblivion. With fumbling fingers, damp with sweat, he found the handbrake. It was enough to stop the Range Rover with a scratching skid.

The necrotic smell was still with him. Stephen caught the vomit in his mouth, scrabbling for the door handle. Flinging it open, he half fell out of his vehicle, giving in to the nausea. His breakfast of coffee and porridge spewed onto the ground between his feet, splashing his smart leather shoes. He tried to breathe.

Stephen’s work boots were in the back of the Rover. He would normally put them on before walking onto the sodden site, but at that moment angry shouts came from his men. He looked up from between his knees to see Big Tam being pulled off Ronnie by the site foreman, Jackie.

Spitting bile into the dirt, Stephen rushed down to help. Mud enveloped his smart shoes and dirty water splashed up from bloated puddles, caking his trousers and soaking his feet through to the skin. Each step felt heavier and heavier with sucking mud, draining the energy from him. Part of him wanted to flee. It cried somewhere in the back of his mind like a terrified child, and for one moment Stephen thought his girls were here crying. But of course, that was a silly idea, and so he dismissed it and forced himself on.

It wouldn’t be the first time an accident on a site had caused a fight, though it was odd amongst this group, who had only ever seemed good-natured to Stephen. Their work had been full of laughter, practical jokes, and banter about football, sex, politics, and even religion, with a Catholic-Protestant division Stephen didn’t wholly understand. Another reason to hurry. There were more months of work ahead. Better to bury the hatchet now than let things fester.

Jackie had managed to calm things down by the time Stephen arrived a little out of breath.

“Right, you two. Enough,” the foreman growled like only a Glaswegian could.

His usual ruddy complexion gone, Jackie was pale. The old foreman looked just like Stephen felt: worried and ill. Stephen saw it in the faces of every person stood on the site. They had aged ten years, and he was sure if he looked in the mirror he’d see the same thing.

Stephen approached, a palm facing each man as if holding back an invisible wall between the two fighting men. Jackie was doing the same but from a position directly between Big Tam and Ronnie, his back to the wall of peat. Jackie was Stephen’s right- hand man. He liked him and hoped to work with him a lot more in the future. They exchanged a perplexed look, gilded with worry on both sides. In the other, neither saw someone who had any answers. There was silence. Things were calming down. The simmering pressure was still there, but the trouble must have passed, whatever it was.

Willie, having come out of his cab in the dead digging machine, exclaimed, “Dear God!”

Stephen knew Willie wasn’t a religious man, though he loved his Celtic FC with a sports fan’s fervour, and yet he said the words like someone facing the reality of their own mortality. They all turned slowly, the sense of dread growing in the pits of their stomachs.

Out of a fallen clod of peat, a disembodied hand protruded, glistening brown like wet leather in the rain.

“What the fuck is that?” Willie said, slipping and staggering over to them.

“It’s a fucking hand,” Jackie growled.

“I can see it’s a fucking hand,” Willie said, panic rising in his tone.

The hand was a dark, leathery brown, and no bigger than a child’s Tilly’s age. The claw of the digger must have cut cleanly through its arm.

As he stared at the dead hand, Stephen was consumed with the idea that he wanted to punch Jackie in the face. He wasn’t sure where that thought came from. He only knew that it seemed like a great idea. Self-righteous prick, always shitting on Stephen’s suggestions, thinking he was the boss.

A noise from behind startled him. He turned to see the protest group brandishing placards. One of them had a hammer.

“Aye, what tha’ fuck are yous hippie cunts aboot?” Big Tam shouted. Although, in his Glaswegian growl, it sounded more like a challenge.

The kindling was ignited, setting the two groups at each other. They ran, meeting Stephen in the middle, who stood with his arms opened wide, shouting, “Come on then, you bastards.”

Stephen, who hadn’t had a fight since he was eleven, threw the first punch, hitting the old woman, Meredith, with the curly, grey hair, so hard her head snapped back. She hit the ground with a massive slap, knocking all the wind out of her, her delicate nose now a crushed smear across her face. Stephen jumped on her, straddling her body, raining down blows on her unconscious face, just as the hammer carried by one of the protesters buried its head in Ronnie’s skull. He stood, twitching for a moment as thick red rivulets ran like oil down his face.

Stephen’s screams of rage only stopped when the two-by-four of a placard caught him clean on the side of the neck. He fell sideways off the old woman, consciousness briefly leaving him. He tried to push himself to his knees again, only to receive a second blow from the two-by-four, spinning his head and dislocating his jaw. He fell face-first into the mud. The blood pouring from him didn’t matter. He would kill whichever bastard had done that to him. He would kill them all. Or he would have done, had the two-by-four not struck a third and final time. It came down with full strength on the vertebrae connecting Stephen’s head to his body. A snap, and Stephen did a brief danse macabre in the mud.

His new life in Scotland was over.

Chapter 3

Not since the accident, since she had lost him, lost almost everything, had they walked through the park to take Oran to school. It had been a year. Autumn in Glasgow was always their favourite time of the year. Mirin and Omar would walk either side of Oran, holding his hands, swinging him between them – when he didn’t want to chase pigeons or stroke a passing dog, that is. It was a time of year that reminded them of meeting at university when they were barely adults and everything seemed possible.

Now, with Omar gone, the piles of golden leaves in Kelvingrove Park looked dead. The portent of a long, dark winter to come.

The little boy ran ahead, wriggling to free himself from his mother’s grip so that he could kick great showers of gold and brown into the air, clapping his hands with the sheer joy of it. This brought a smile to Mirin’s face. He was the only thing she had left, the only thing she lived for, and the only thing during the long nights in the last twelve months that had prevented her from joining her beloved Omar. This was her most private thought, something Mirin had never shared with anyone, not even her grief counsellor.

They came out of the park on to Gibson Street, turning right to walk past the short parade of coffee shops, bars, and restaurants, up to Oran’s school at the crossroads. Behind that, the university spread up and over Gilmore Hill.

Mirin swallowed the ball of anxiety in her throat. She could see the other parents dropping off children in cars or walking together in small groups. School had been going since August. Now, early October, Oran was starting back late. This would be his first day at school in more than a year, and Mirin’s first day back to work as well. She had talked it over with her counsellor. Apparently, it marked a big step in her grief and was an indication of the real progress she’d made. Intellectually, Mirin understood that actions sometimes need to precede belief until the mind could catch up with the body. Mirin never had trouble understanding things intellectually. That was her job, a job that up until a year ago had been so important. But the physical part, the actual doing that her counsellor was keen on, well, she guessed she had to take in one clichéd step at a time.

The noise of children in the playground grew to a crashing wave. Mirin’s heart leapt, feeling as though it might fall forever if she didn’t catch it with another hard swallow. She squeezed Oran’s hand.

Nearing the gate, Mirin could feel him wanting to pull away again and run to see his friends. The other parents were looking at her. She needed this. Oran needed this.

Mirin wanted to hug her son and tell him how much she loved him. She crouched at his level. His hair was snaked in tight curls. His brown eyes stared back at her. She would tell him that everything was going to be all right.

But Oran spoke first.

“Are we getting back to normal now, Mummy?”

“Yes, my little darling, we are.”

“Will it ever be normal again without Daddy?”

Mirin held back the tears threatening to boil over.

“No, I don’t suppose it will, darling.”

“We’ll just do the best we can then, Mummy.” The little boy gave his mother a hug, throwing his thin arms around her neck.

“Yes, we will,” Mirin said, marvelling at the child’s resilience. “Now, you have a great first day at school.” She closed her eyes, planting a kiss on his forehead. It felt warm and real. He let her go with one last squeeze and ran into the playground amongst the other children shouting back over his shoulder, “You have a great first day too, Mummy.”

Mirin watched him for a moment, then that ball was in her throat again. She looked up the hill to the main campus of the university. She had got through the first hurdle. Now all she had to do was keep going, one hurdle at a time, until the day was done.

“Professor Hassan, how good to see you.”

Mirin stiffened. It was Mrs Stewart, the deputy head.

“We all wanted to let you know how devastated we were when…”

Mirin couldn’t do this right now.

“Thanks,” she said. “Can’t stop. It’s my first day back. Thanks again. Sorry.” Mirin had already started up the hill at pace, leaving the school behind her.

Mrs Stewart’s quizzical look disappeared the second Toby McBride pushed over Sally Pinker.

“Tony McBride, come here at once.”

Mirin didn’t look back. Now all she had to do was get through a day in the archaeology department. With any luck, she could spend the next week just going through a year’s worth of emails.

Chapter 4

Constable Hardeep Bhaskar, or Dip to nearly everybody, was doing his usual beat, stopping in at various places. It was good to touch base with the community: shop owners, farmers. He’d pick up a coffee from the shop, which doubled as a post office, and maybe one of those Danish pastries they had too. He shouldn’t but he usually did, resulting in the slight belly his mother always chided him about.

“You can let yourself go after you’re married, Hardeep.”

She meant well and it wasn’t as if he wasn’t in the market for a wife. The opportunity just never seemed to present itself out here in the countryside. Dip wasn’t exactly lonely, but he had found himself softening to his mother’s occasional hints about potential arrangements she and her cousins had been scheming about for years.

Whether it was a result of solitude or not, Dip liked this part of his job: getting everyone to know his face. He tried to give out a friendly persona so people felt they could talk to him. It was also one of the big pillars of community policing. Managing rural crime without the cooperation of locals would be nearly impossible.

The next stop was one of his favourites: the small road development at the nature reserve, where a little protest had camped out ever since the project started. It was very good-natured on both sides, which made a refreshing change from the vitriol he saw more and more on the news these days.

Coming down the road, Dip noticed that the protesters were no longer there. His initial thought was that they must have moved on, maybe to a new, bigger threat to the environment. There was a little piece of him that was sad at that idea. There wouldn’t be a reason to come by regularly and see how everyone was getting on.

The indicator on his police car clicked rhythmically as he slowed down to make the turn into the site. Something seemed a little out of place. A couple of placard tops lay discarded on the ground. They had been torn off and the sticks left as careless litter. Flasks of tea were scattered around the once-campsite, plastic cups surrounding them. Usually they were placed neatly bottom-down. Surely the environmentalists would tidy up after themselves?

Of course, they wouldn’t be the first group of hypocrites he’d ever met. However, they hadn’t struck Dip that way. They’d seemed an honest and sincere bunch, not protesting for the sake of getting riled up, but with a genuine cause they were prepared to quietly advocate for. It was a pity, but once he tracked them down, he would have to write them up for the violation. He allowed a small sigh at the thought of the paperwork.

His suspicions were confirmed as soon as he turned off the main road. The project manager’s Range Rover wasn’t parked up in its usual spot. Instead, it sat abandoned in the middle gravel access road, its driver door left open. The large vehicles beyond were uncharacteristically still. By this time of morning, the digger was normally in full swing. The place normally resembled a veritable hive, trucks and diggers crawling around carrying their payloads of dirt and minerals. All lay silent.

Dip parked up behind the Range Rover and got out. The thought crossed his mind that he should call it in, but what would he say? What was he calling in? He didn’t know anything yet. He’d have to go down and check. Gravel crunching under foot, Constable Bhaskar approached the Range Rover. Glancing inside, he saw nothing untoward. Then his eyes found the carnage ahead.

Reflexively, his hand went to his radio. Nothing happened. A hollow button-click. There wasn’t even any static. He clicked it again, and still nothing. Eyes scanning left to right, he walked down towards the site, still trying his radio for dispatch. Dip could see bodies lying on the ground and slumped against vehicles, their limbs at funny angles, heads slumped, necks twisted, and blood. So much blood.

Click. Click. Click. Still no answer. Blood pounded in his ears. Dip slipped and stumbled through the mud until he reached the first body.

What might have been the old lady lay face up next to the body of Stephen, the project manager, who was face down in the mud. Dip felt bile rising and his stomach clenched; he brought a hand to his mouth, fearing the retch. The old woman’s face was unrecognisable, nothing but red pulp. Only her curly grey locks identified her as Meredith.

Stephen’s head was turned sideways, eyes staring blankly. His neck looked as though it had been broken, leaving an unnatural valley between the back of his shoulders and the base of his skull. His jaw was dislocated, twisted into hyper-extended palsy.

Dip couldn’t hold it back any longer and vomited on the floor next to Meredith. The constable straightened up, wiping his mouth. He needed to take in the details of the scene but all he wanted to do was un-see the tableau of violence. He noted Ronnie’s body: brains spilled out of his skull. The body of Big Tam between two dead protesters, Sam and Ollie, a pickaxe buried between the big man’s shoulder blades. Willie lay slumped against the wall gouged into the peat, frozen, eyes staring wildly.

A small movement caught Dip’s eye. It was the young girl, Susie. He ran to her, falling to his knees, mud drenching his uniform. She was breathing, though the breaths were shallow and rapid; one of her eyes was swollen shut. Her nose was broken, as were several of her fingers. In places, her clothes were torn, suggesting another kind of physical violence Dip didn’t want to contemplate. He took Susie’s mangled hand. She looked through him, as though he wasn’t there. Taking one last ragged breath, her chest rose and then her body went limp. She exhaled in a long, slow, ghostly gasp, and she was gone.

His mind snapped back to the radio but it was still useless. Click. Click. Click. He was beginning to hate that sound. It was the mocking sound of futility.

“Christ!” he said out loud. Dip tried to gather his thoughts and make sense of it all. Overwrought with emotion, he needed to draw on all his training and follow procedure to take control of the situation.

Bodies were everywhere. It was like a damn battlefield. The two sides had seemingly gone to war, killing each other with their bare hands or whatever tools they had available: two-by-fours, hammers, pickaxes, screwdrivers… But to what end? It didn’t make any sense. It had been all so good-natured. What could have happened to make them want to kill their fellows? Dip searched and found no answers. He clicked the button of his radio once again to no avail. He called desperately into the silence for someone to answer, “Come in. Is anyone there, please?”

Somebody answered.

The shuffle of muddy boots came from behind the JCB digger. Dip turned and saw Jackie, the foreman, covered in blood, holding a crowbar. He had hate in his eyes and slashed across his face in a slicing grin. Jackie raised the crowbar over his head.

“Fucking Paki,” Jackie growled through broken teeth and a mouth full of blood.

Dip hadn’t been called that in a while, probably not since he was a probationary officer arresting drunks on a Friday night. The words gave the officer an emotional stab, picking at a lifetime of unseen scars: from the playground, on the bus with a group of mates, random insults walking down the street, even a joke he’d overheard in the changing rooms at work years ago, and which he’d never complained about. And that wasn’t the half of it. Not really.

The crowbar had already begun its downward swing. He raised his forearm in a protective upward block, and the crowbar connected. The impact shattered his arm, but saved his life.

Dip rolled away, trying to put space between him and Jackie, who was already bearing down on him for the second swing. The sodden ground slipped under Dip’s boots. He felt like a cartoon character, wheeling his legs on the spot and getting nowhere.

Scrambling past the metal bucket of the JCB, Dip’s back came to rest against the caterpillar track. There was nowhere else to go except for maybe under the earth mover, but time had run out. Jackie came on slow and steady and had closed the distance, repeating his racist slur. He spat the words with victorious intensity, which belied every single interaction Dip had had with Jackie.

Dip fumbled one-handed with his utility belt. Jackie raised the iron bar above his head to finish off the constable. There was no time for the verbal de-escalation they had all been taught in the academy. It was now or never. Jackie took one final stride forward. Dip pulled free the canister from his belt and lifted it as high as he could, depressing the button on the pepper spray. The jet of burning liquid shot out of the canister into Jackie’s face. The foreman cried out in pain, dropping the crowbar, which hit him on the back of the head.

Bringing his blood- and mud-caked hands to his face, Jackie staggered, thrashing side to side. Blinded, he slipped. With his hands engaged with trying to clear his eyes, Jackie didn’t put his arms out for balance and so his entire body pitched in the air and fell back heavily to the ground. His skull landed on one of the upturned teeth of the earth mover’s bucket. There was a wet crunch of shattering bone. Jackie’s body convulsed as though in protest of his sudden death, legs and arms giving involuntary twitches.

Dip approached the body cautiously, holding his broken arm to his chest. Jackie stopped twitching, as dead as all the other bodies on the site. What Dip suspected was brain matter dripped glutinously out of the back of Jackie’s skull and on to the muddy ground.

Dip began to shake. His arm was numb with shock and he found himself panting involuntarily, unable to pull in enough air. Every fibre of his being was telling him to run away, to get as far away from here as possible, but his training told him to take control of the situation, that people were relying on him. But the situation didn’t need controlling any more. Everyone was dead. Fucking hell, they were all dead, and he had just killed a man.

He looked around, as if hoping to see an answer in the carnage.

That was when his eyes, which had seen too much for one day already, alighted on something that somehow appeared incongruous even in these horrific circumstances: a severed hand, a small and delicate and leathery brown hand.

Buried in the bank, at about the same level as Ronnie’s chest, concealed deep within the peat, was the face of a young boy, his eyes closed as if he were asleep. Tangles of black curly hair were plastered to his beautiful face.

Constable Hardeep Bhaskar could not draw his gaze away from the face of a beautiful boy entombed in the wall of peat. He was perfectly preserved, but for a dark leathery brown to his skin. Lying peacefully on his side, he looked as though he was merely sleeping, his face miraculously untouched by the earth mover’s claw.

As Dip stared at the sleeping visage, fear began to grow in his heart, rising like a wall of black water about to crash down over him like a wave.

TO READ MORE YOU CAN FIND NEOLITHICA IN EBOOK, PAPERBACK AND HARDBACK ON AMAZON