Guest post by editor, author, poet, and generally excellent guy, Joseph Sale

When writers, editors, and critics discuss world-building, it is often in isolation. But to tell a successful story, world-building must be intimately interlinked with two other elements: plot and character. In fact, these three should be so tightly interwoven that it is almost impossible to divorce any single element.

The best example I can probably give is to be found in The Lord of the Rings.

The dark lord, Sauron, has bound his spirit to the One Ring, and thus, to prevent his return, the One Ring must be destroyed. This is the basic premise of the story. However, if the One Ring could be destroyed by any hammer or fire, there wouldn’t be much plot here at all. Frodo could have tossed the Ring into the hearth at Bag End and that would be the end of the “epic” adventure! But of course, the One Ring cannot be destroyed that way. It was made by a master-craftsman demigod in the fires of Orodruin, and only there “can it be unmade”. The world-building informs the details of the plot. Without the interaction of the two, there is no real story. Combined, the plot quite literally “thickens”.

Now we must add to this a third all important element: character. This is also intimately tied to the world-building. We know that the One Ring, as well as being near indestructible, also has addictive and corrupting properties. Therefore, to give the Ring to a mighty warrior or a powerful wizard would be a grave mistake, one that would endanger all of Middle Earth. Thus, the Ring has to be given to a humble hobbit, one who will be not be corrupted by its power as quickly as Glorfindel or Aragorn or Elrond or Gandalf. The journey to Mordor would have fairly interesting were it made by one of the aforementioned heroic types, but made by, as Galadriel words it, “the smallest person”, made by a hobbit, the journey becomes truly extraordinary and mythological in its proportions.

There are many other reasons why Frodo is the ideal ring-bearer, including his strange mirroring of the Dark Lord himself, but as Michael Ende would say: that is another story, and shall be told another time. Suffice to say, this briefly sketched example illustrates how the truly timeless and epic stories of our canon wield these three key elements as one, combining their properties with the magic of narrative alchemy. If we remove any one element from The Lord of the Rings, its integrity is significantly reduced if not outright destroyed. Thus, when we talk about “building a world” we really mustn’t isolate this from the other elements, but understand that plot, character, and world are all exerting bi-directional influence upon each other. Our characters are the product of the world they live in, as well as influencing that world in turn with their actions. The plot arises as a result of the world and its circumstances and conditions, but the plot also carves out a relief of the world for the reader so that it may be comprehended, the same way that the valley carving a way through the landscape allows us to perceive the mountains. Without mountains, valleys cease to exist, and vice-versa.

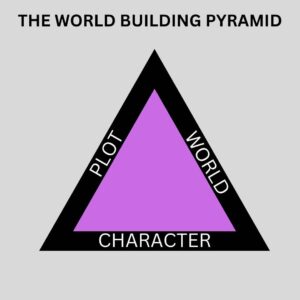

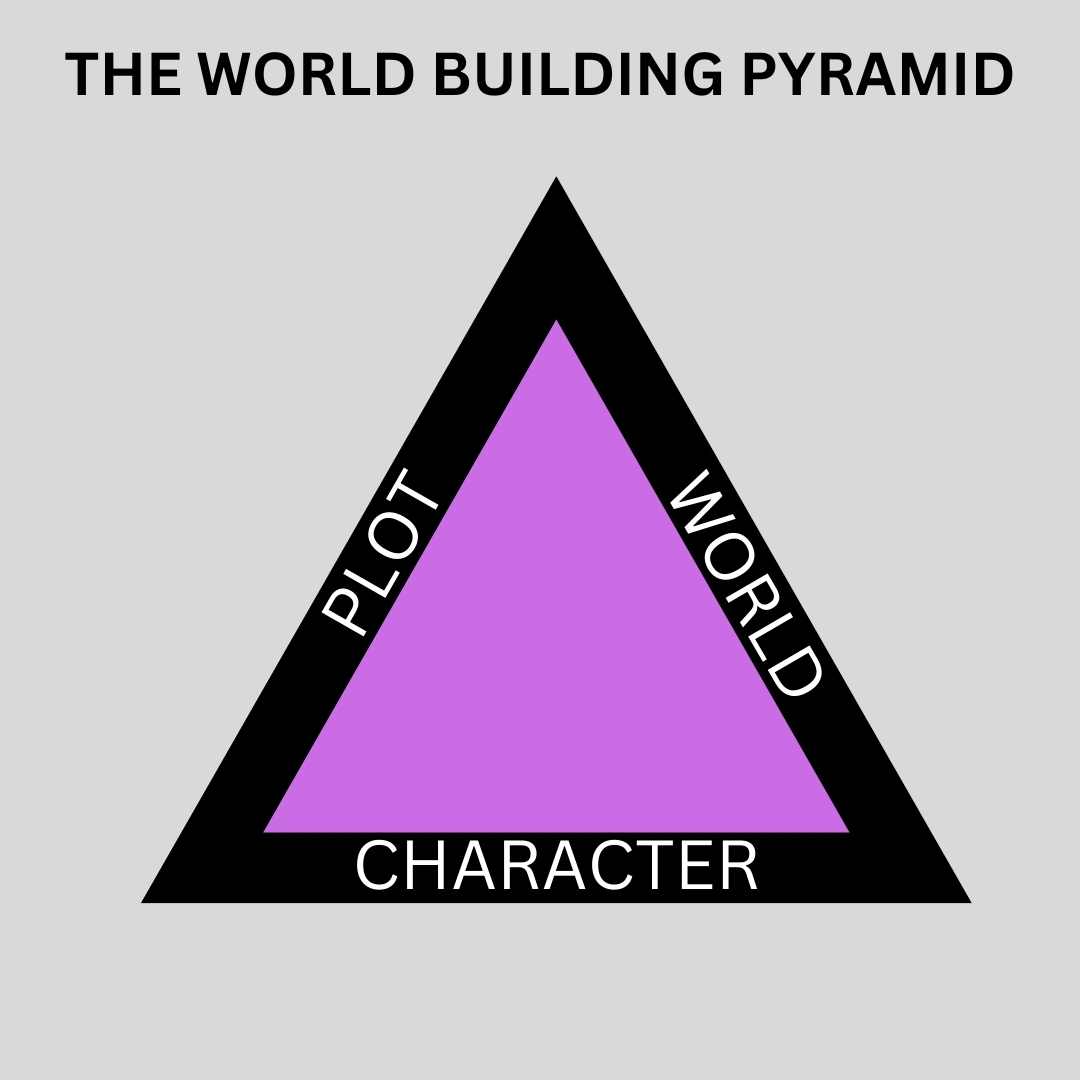

This interconnected trinity might be pictured as a pyramid or triangle, with each element resting at one of the three points. The intersection of the three creates a stable structure that endures for millennia. Indeed, trinities are the foundation of all of existence. Matter has three states: liquid, gas, solid. Time is divided into three regions: past, present, and future. The mind  operates in three states: waking, sleeping, and dreaming (or conscious, unconscious, dreaming). Freud’s model of the psyche was threefold: ego, superego, and id. Even God is said to have three aspects: Father, Son, and Spirit (this is mirrored in more than one religion). Indeed, in critical discourse, arguments usually follow the pattern of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and this is used in some narrative structures, though I personally believe a five-act structure is more suitable for narrative (but that is another story, and shall be told another time).

operates in three states: waking, sleeping, and dreaming (or conscious, unconscious, dreaming). Freud’s model of the psyche was threefold: ego, superego, and id. Even God is said to have three aspects: Father, Son, and Spirit (this is mirrored in more than one religion). Indeed, in critical discourse, arguments usually follow the pattern of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and this is used in some narrative structures, though I personally believe a five-act structure is more suitable for narrative (but that is another story, and shall be told another time).

So, in short, systems in which three forces or elements intersect often provide stability. To court controversy by quoting Amazon’s Rings of Power, “One corrupts, two divides, but with three there is balance.” There’s great truth to be found in these words.

But now that we know this, it can be quite daunting—paralysing even—to contemplate planning a story. After all, how can one create characters when we have yet to think of plot? How can one create a world without characters to go in it? Surely these things don’t all arise at once?

As always, the answer lies in myth and ancient teachings. In Hindu theology, the creation of the world was actually an act of dismemberment, the unity of the original One divided and compartmentalised into separate (though still connected) forms. Jewish Kabbalah explores similar ideas with the sephiroth or “emanations” on the Tree of Life. This is, of course, the fundamental basis of non-duality and magick (but that is another story, and shall be told another time).

Hindu theology brilliantly reflects the truth of the creative process, for often the act of creation is more a re-assembly of an existing blueprint—a blueprint that exists in the unconscious, or Plato’s realm of Ideal Forms, or in the sephirotic archetypes of God’s dreamspace, whichever is more palatable to your sensibilities—than the conjuring of previously non-existent forms into being. Thus, it’s our role as creatives not to try and come up with this beautiful interconnected system wholesale, for that would tax our minds beyond their limits, but rather to ask the simple question of, “How are these two seemingly disparate things connected?”

This question is really the same one asked by children as they play. They have two toys, and they ask the question, “What happens if I play with them together?” Or they have two coloured paints, and they intuitively mix them to see what comes out. Children are forever combining and recombining materials like little scientists. When we imitate them, we can discover surprising truths.

So, how do we begin to unearth the “blueprint”? How do we figure out which fragments belong together, and which fragments are maybe part of some other mosaic?

In my writing craft book, The Divine, I advocate for creativity as receptivity. Not straining with the intellect after plots or characters, but rather working to become a receptacle of divine imminence, the true wellspring from which creativity springs. If this is too spiritual or religious for you, consider how all your best ideas come when you are either in the shower, about to fall asleep, or when your mind is wandering on a completely obscure topic. The brain does its best work when it’s not actively grabbing for information, but instead relaxed (aka, listening and receptive to what is coming up, rather than dwelling on or reaching for information). If you need to remember something you’ve forgotten, the worst thing you can do is “wrack your brain”. It’s when you stop searching for what you lost that the memory returns. If I still haven’t persuaded you, consider the words of Philip Pullman, a diehard atheist: “What I seem to be saying here, rather against my will, is that stories come from somewhere else. It’s hard to rationalise this, because I don’t believe in somewhere else…” (Pullman, Philip; Daemon Voices; “Magic Carpets”; David Fickling Books; 2017.)

So, we’re posed with a serious challenge as creatives. We have to be relaxed enough to receive the initial spark of inspiration and story, but we also have to be alert enough to recognise it when it comes, to begin to act on and transcribe it, and also to perceive the connections between dispirit elements.

Block by block, we build the pyramid, working from the three corners inward. If we discover something new, then we firstly have to ascertain which element it belongs to (plot, character, or world) and then how it interacts with the other two elements. If we are uncertain where it sits, then perhaps we are truly beginning to work our way towards the secret chamber at the heart of the pyramid, where the trinity become one, and great storytelling can occur. If we cannot see how, for example, a character might intersect with the plot and world, then likely they belong to another story, or might form more of a background texture to the tale you are currently telling. Stephen King once wrote, “All things serve the beam.” (The Dark Tower). All things must be in their proper place to serve the story. Every element is interlocked and upholds the heart-centre (in King’s case, the Dark Tower itself).

Whether you are building epic fantasy worlds, criminal undergrounds, or lambent neighbourhoods full of quirky lovers, the principles remain the same. Love stories can only take place in environments that facilitate lovers meeting. Likewise, crime stories take place in criminal worlds, which are as alien to most ordinary people as the baleful landscapes of Saturn. Of course, interesting things begin to happen when you play with expectations (again, like the child messing around with ingredients). For example, what happens when a killer shows up in a gentle neighbourhood? Where does the killer come from and why does he leave his own world and show up in this one? The killer is going to exert a lot of influence on this new world, because he fundamentally doesn’t belong—like a cancer acting upon the healthy body. That’s character and plot intersecting with world already! We managed to get here by simply asking questions.

But let’s take this one step further. Clive Barker once wrote, “Memory, prophecy and fantasy – the past, the future and the dreaming moment between – are all one country, living one immortal day. To know that is Wisdom. To use it is the Art.” (Barker, Clive; The Great And Secret Show; William Collins Sons & Co Ltd; 1989.) Memory is the world, our past. Prophecy is the plot, what our heroes are destined to do. And the dreaming moment between is made by our characters, who undergo profound changes as both past and future act upon them in the eternal lived present moment. If we conceive the triune model in the light of other trinities, such as time (past, present, future), discourse (thesis, antithesis, synthesis), and divinity (Father, Son, Spirit) we unlock even deeper avenues of exploration in constructing our narrative pyramids.

In the case of time, we understand how each element might be exerting influence on the other. For example, to conceive of the “world” your characters inhabit as “the past” is to understand it not as a static place or space they inhabit but a textured realm of memory and emotion. Similarly, to conceive your characters as “the present” is to understand they are not passive receivers of experience but rather their actions in the here and now will shape the future (aka, the plot). The future influences the present moment, because we alter our actions based on our expectations of what is to come. Likewise, the past influences the future, because our traumas and experiences shape who we are now—ie., who we are acting in this present moment.

No better is this reflected in all of literature than in Dante Alighieri’s threefold model of the cosmos: Hell, Purgatory, Heaven, found in The Divine Comedy. In Hell, the sinners are trapped in the past. They cannot move forward. In Purgatory, the sinners have gained self-awareness and therefore can act and change. Purgatory is the only place where time moves forward. Indeed, it is in Purgatory that we encounter this startling quote,

“ Perceive ye not that we are worms, designed

To form the angelic butterfly, that goes

To judgment, leaving all defence behind?

Why doth your mind take such exalted pose,

Since ye, disabled, are as insects, mean

As worm which never transformation knows?”

(Alighieri, Dante; Purgatorio, Canto X.124-29; Translated by Robert M. Durling).

Past, present, and future are all encapsulated in these lines, along with the idea that it is in Purgatory, the present, that transformation can take place. In Heaven, things once again become fixed, but the difference is that a synthesis and transformation has occurred, and the sinners—for there are still sinners in Heaven—have now integrated their shadow selves and therefore reached extasis: the Promised Land, aka, the future.

Ultimately, if we want to build better worlds and better stories, we have to wield these three powers in harmony. Doing so will allow us to construct stable towers and pyramids, where all the “beams” map inward to support the centre, instead of creating a disjointed landscape of random events, characters, and places that fall to pieces at the first gust of wind. Of course, achieving this is not easy, and though we have covered some basic and simple techniques for approaching this unity, there is an almost infinite depth to this subject. For those who would, as Clive Barker puts it, wield the Art, there are no shortcuts, only the continual exploration of the triune forces of existence itself, which in truth are the triune forces residing in the very human soul.

To read more about crafting narrative, you can purchase Joseph Sale’s writing craft book The Divine for only 99c on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0B46D63BF

You can also gain access to a free book by Sale, and updates from his blog, by signing up to his mailing list: themindflayer.com

James Sale

Brilliant analysis – rich, insightful and useful. Love the Pullman quote against himself!

Christa

Joseph Sale’s articles are never just about how to write. They are about how to live as a true creator. I loved this topic. We don’t often think about the world’s part in the story. It’s almost its own character. Thanks for posting this, Dan!